No one can understand the world without an understanding of the state, and of classes and class struggle. Under the capitalist mode of production, the principal classes in society are the capitalist class and the working class. Their historically-determined production relations form the basis, the economic structure of capitalist society. The capitalist class owns the means of production, the workers work for this class for wages; having no means of production of their own, they are forced to sell their labour power for what they can get. They are thus an exploited class. The state is part of the superstructure erected on the basis of capitalist production relations to reinforce the power of the capitalists to exploit the workers. In the Communist Manifesto, Marx wrote: ‘The executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.’ Whichever party may have gained the most seats at election time, the capitalist class still constitutes the ruling class and consequently, the capitalist system is still dominant. The state is an organ of class rule, a machine for the oppression of one class by another. Under capitalism, it is organised violence against the working class. It is the main weapon of the capitalists for maintaining their class rule and the privileges which stem from it. And history bears out the truth of this conclusively.

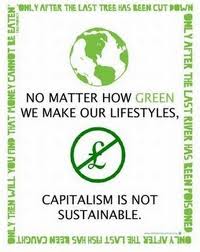

Capitalism inevitably produces exploitation and poverty, war, the oppression of women and 'minorities', poisonous environmental pollution, and the waste of human and natural resources, none of which can be consistently eliminated without the socialist transformation of society. Many like to paint the ideas of the Socialist Party as no more than a hopeless dream or even a nightmare. Let us face the facts and that is that the education of the masses is a large and strenuous task, but there can be no socialism until the people desire socialism and strives for socialism. The Socialist Party cannot take part in the work of socialist education till we are ourselves deeply imbued with the socialist ideal and our thoughts and our desires are constantly turning towards the system of society in which the land, the means of production, and distribution are held in common, where production is for use, as and when required, not for profit, exchange or sale and the organisation of production and distribution is by those who do the work for the general welfare and mutual harmony with the other workshops producing the like utility, also with those of all. The Socialist Party declares that the victory of socialism will be achieved only by the independent revolutionary class struggle of the workers against the bourgeoisie and the bourgeois state, only by the abolition of the capitalist state and the entire capitalist order, by the building of worker’s power and the construction of a world socialist society.

The capitalists like to pretend that capitalism is eternal. The fact is, however, that for the greater part of human history mankind lived in tribal society under a system of primitive communism, a system without classes, in which acceptance of the authority of the elders did not require a special coercive force but was freely given, and questions of paramount importance were decided by the tribal assembly. In those times there was no state. Nor did the notion of male superiority exist. Women took part in decision-making on terms of full equality with men. They had an honourable place within the tribe, not only because they did their full share of work on an equal footing with the men, but also because the only sure way to reckon descent was through the mother. It was the development of private property giving rise to the problem of individual inheritance which in turn brought about a male-dominated type of family – the patriarchal family – the emergence of which Engels described as ‘the world-historic defeat of the female sex’

Marx and Engels advised the workers to unite in trade unions and fight for improved wages and shorter hours. In these struggles, victories would be won. The workers could wring concessions out of the capitalists. ‘Now and then’, the authors noted in the Manifesto, ‘the workers are victorious, but only for a time. The real fruit of their battles lies, not in the immediate result, but in the ever-expanding union of the workers.’ Better living standards could be won by trade union pressure, as by political agitation, to secure such improvements as the Ten Hours Act. But such gains would be meagre, precarious and temporary. As Marx answered Citizen Weston, though real wages could be increased here and there by trade union activity, ‘The general tendency of capitalist production is not to raise, but to sink the average standard of wages.’

The system is rooted in the exploitation of the producer by the property owner, as was every previous system since the birth of civilization. Unlike previous systems of class exploitation, however, capitalism had developed the productive forces to a point which renders the existence of classes unnecessary. Private property alone stands between mankind and the fairly rapid advance to an age of abundance.

Poverty, in itself, has never been a cause of revolution. (Otherwise, revolutions would happen every day in some part of the world.) That capitalism will waste and misuse resources is not seriously in dispute. But the waste and misuse of resources, though it arouses opposition and generates pressure for social change, does not in itself create revolutionary situations. But Marx believed that impoverishment, the incompetence of the ruling class ‘to assure an existence to its slave within his slavery’, a forcing down of the level of life through economic crisis, seemed, in the mid-nineteenth century, an essential pre-requisite for proletarian revolution.