Near-future science fiction frequently explores the possibilities of imminent technologies – gadgets that haven’t been designed yet but could be given recent real advances in technology and design. Whilst its track record on such predictions – such as us getting to Mars by 1977 and everyone having flying cars – have been a bit wide of the mark, others have been much closer and in fact actively conservative compared to the real historical record. Scientists can be very far-sighted but at the same time have only a very narrow field of view, like a blinkered racehorse.

William Morris's News From Nowhere famously describes a deliberately low-tech socialist society in which people have eschewed the benefits of technology and adopted simple ways of doing things, although arguably he cheats by powering his 'force barges' with some mysterious energy source he never explains, thus hiding his technology rather than really abolishing it. Nonetheless, this is unusual in that most portraits of the future, whether socialist or not, depict a society of advanced technological splendour in which all our needs are met by a range of technical apparatuses only a voice-command away. The amount of electronic appliances in the average household now massively outweighs that of fifty years ago, and half a century from now we may shudder at the poverty of gadgetry suffered in the early 21st century. But it is not necessarily the case that a socialist society will produce an equal amount of high-tech gadgetry. Because socialist production will meet real rather than false needs, it could be that socialism might be a low-gadget society. Although mobile phones, Ipads, laptops and so on can satisfy some actual needs, it is mainly sociologically - and psychologically - induced perceived needs they actually satisfy, such as the need for conforming to group norms, the desire for prestige, and the belief that a product brings contentment. And because these items are produced to satisfy manipulated needs, they can have little use-value. So if socialism will be a society that relies far less on gadgets, it is only because it will be a more honest society than the present one, without artificial needs.

Most people have no direct experience of science, only of the technology that is an almost incidental by-product of it, yet capitalism pours billions into pure scientific research despite the fact that virtually none of it will ever yield a profit. Why? Because the one per cent that does make a profit will pay for the 99 per cent that doesn't. In capitalism, science is a huge gamble that only occasionally results in a win, but bets are never placed on research that helps people who can't pay.

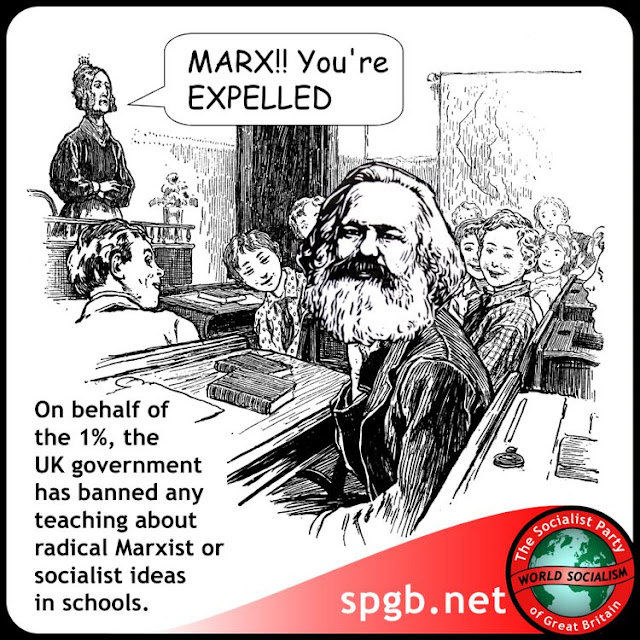

Scientists do have their heroes, but they don't worship them as infallible gurus because it is recognised that argument from authority is inferior to an argument from evidence. Socialists take the same view of Marx and other revolutionary thinkers. Non-market, non-hierarchical socialism, which has no such agenda and which can therefore collectively determine the best course of action based on the available evidence. In science good ideas are not taken seriously enough when they come from people of low status in the academic world; conversely, the ideas of high-status people are often taken too seriously. The scientific method suffers because science is organised hierarchically. The problem with science in capitalism is that scientists have mortgages to pay, so they need to chase funding because they can't afford to work for free.

"Science uses commodities and is part of the process of commodity production. Science uses money. People earn their living by science, and as a consequence the dominant social and economic forces in society determine to a large extent what science does and how it does it."(The Doctrine of DNA by R.C. Lewontin.)

And what will socialism do with pure research? Carry on the same way? Hardly. What we can say for sure is that curiosity is not likely to be dimmed by some inexplicable post-capitalist apathy in a society that releases scientists as well as all other workers from the compulsion to direct their efforts towards only those endeavours that the capitalist class sees an interest in funding. So what approach would socialist society take to the great scientific project? Priorities would certainly be different. Drug research, for instance, will not occur in capitalism if the R and D cost is not likely to be recouped, thus diseases rife in poor countries are overlooked while popular research projects are based on global sales estimates such as anti-depressants. Much of the pharmaceutical industry would be obsolete or transformed anyway if one can assume, after capitalism, a dramatic fall in heart disease and obesity, two wealth-related conditions for which the present drug market is principally geared, and an even more dramatic fall in poverty and stress-related diseases which presently do not even merit scientific attention. Similarly, science would no longer be prostrate at the feet of the military where global military spending is in the trillions. While some other lines of research would probably end, for example, cosmetics, including most animal testing which is for this purpose, there would be a clear need for continued work in climatology, energy, epidemiology and many others, but it is questionable whether a socialist community would have the same passion to send humans to Mars or to build space hotels. In socialism, science will still be a gamble, but with the difference that no knowledge thus gained can ever be money lost. It may be that the huge time, resource and work investment in such projects as Atlas and the Large Hadron Collider, the LIGO gravitational wave detector or the AMANDA neutrino telescope will continue in socialism, but if they do it will be because the population understands and respects scientific enquiry for its own sake, and not because they are expecting to get a new groovy gadget out of it.

The freedom from patent and copyright restrictions, which are forms of private ownership and will thus be abolished, will almost certainly unlock a tidal wave of new development which may revolutionise areas of science that are currently at a near-standstill, for instance, drug research and computing. In addition, the justifiable fear of what corporations, governments and the military might do with horizon science will no longer hold back developments in gene research and nanotechnology.

Lastly, the ending of male domination of science, in which men are four times more likely than women to be scientists will produce a vast influx of new talent and new ideas that can only advance scientific effort for the acquisition of knowledge and ultimately the betterment of humanity.

There are times, though, when even some scientists start to sound a little reactionary, self-righteous and sanctimonious on their own account. One such instance is the issue of animal rights. Scientists tend to be very defensive about animal research, but their arguments, that such research is always necessary, tightly controlled, responsible and largely painless, are at best questionable and sometimes plain wrong, depending as they do on an idealised representation of scientific research as it is supposed to be, and not as it actually exists in the dollar-hungry world of capitalist corporations. Scientists do not help their own case with simplistic no-brainer dilemmas like “your dog, or your child”, which imply that all testing is for the common good and which gloss over the large proportion of experiments done for cosmetics, food colourings, and other non-health-related products.

Socialists are not unduly sentimental about animals and consider that a human’s first loyalty should be their own species. Nevertheless, the degree to which human society is ‘civilised’ can reasonably be gauged by its treatment of animals and the natural world as well as by its treatment of humans, and socialism, in its abolition of all aspects of the appalling savagery of capitalism, will undoubtedly do its part to abolish all unnecessary suffering by non-human sentient creatures. Even in socialism, where there would be little likelihood of animal testing for non-medical purposes, e.g. cosmetics. Socialist science would (if it decided to do so at all) conduct animal research only under conditions of strict and peer-assessed necessity, and with attendant informed public debate, two key factors notable for their general absence today.

Technology is often seen as either the salvation or the scourge of humankind. Some of us are inclined to be technophiles and others techno-sceptics and others a bit of both. That is not to say, though, that the case for socialism rests on developing technology. It is neither possible nor desirable to abolish technology. Without it, we would have to go back to a much harsher form of living. Few people would deny that among the changes technology has brought there have been tremendous improvements to our productive capabilities, if not always to our personal circumstances, or that in a socialist society modern technology will be vital in making sure everyone gets adequate food, housing and medical care. What is required is to change the basis of society so that technology can be developed and applied in the interests of the majority. Neither nanotechnology nor genetic modification is required for socialism. Socialism will take, adapt and use technology as it finds it. What socialism must do, however, is change our relationship with our tools, so that we can take control of our own destinies.